ENJOY 15% OFF A NEW SUBSCRIPTION

Getting to the bottom of Recyclable, Biodegradable, and Compostable

Slang, jargon, lingo, vernacular, parlance, or terminology. Why is it that the words we use in the world of sustainability come under such scrutiny? Often, a word we perceive to mean one thing can actually mean something very different. Even the word sustainability is loaded with various meanings and associations depending on how and when it is used.

I’ve seen industry professionals argue against using the terms sustainability and sustainable because to some these words mean ‘trying your best to do the right thing’, whereas to others they mean ‘effective management of finite resources’, and to others, they just signify ‘well-maintained’.

In this article, we want to cover the three words that pop up most often here at Halo, words that are inherently associated with our product and what we are trying to achieve. These three words are recyclable, biodegradable and compostable.

Recyclable: What does it mean?

The simple answer is ‘something that is able to be recycled’.

The more complex answer is that if a material or object is recyclable, it is able to be used again as something new after industrial reprocessing.

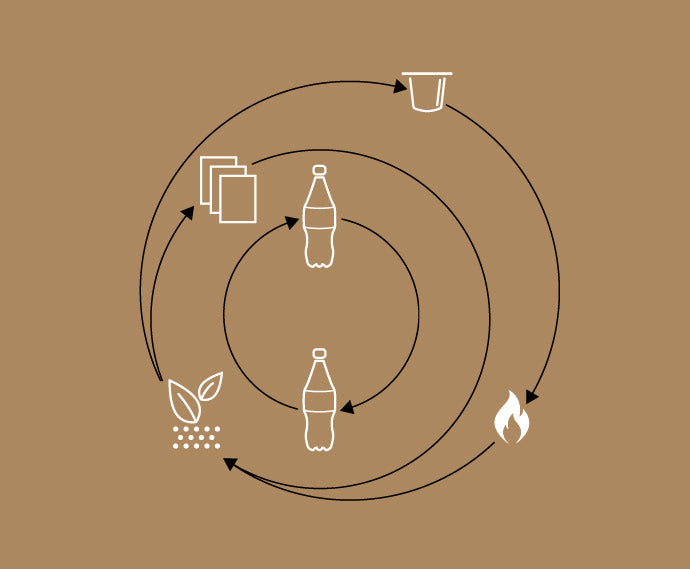

Plastic bottles can be recycled into new plastic bottles. Shampoo bottles can become children’s toys. Glass can become a useful construction material. Cardboard can become affordable toilet paper. This is what recyclable means, although it’s important to know that many recycling processes require the input of virgin materials to make new products.

So, what doesn’t recyclable mean?

Firstly, recyclable and recycled are often confused, namely because the symbols are so similar. Recyclable is shown in the form of a three-arrow triangular Mobius loop, whereas recycled is also shown in the same form, but this time it’s on top of a filled-in circle. There’s clearly an issue here that goes beyond wording.

Recyclable also doesn’t mean recoverable. Whilst cardboard, paper, glass, and some plastics and metals are recyclable, food waste, wax, ceramics, used paper towels and napkins, and mirrors, for example, are not. These non-recyclable items may well be recoverable, which means that through anaerobic digestion, incineration, or pyrolysis, there is an alternative industrial process that can recover energy from them.

Recyclable also doesn’t mean problem solved. Just because something can be recycled, doesn’t mean that it will, because it places the responsibility primarily on the consumer to ensure that the waste reaches a recycling point so that it can become a resource.

So, are Halo’s coffee capsules recyclable? No, they aren’t. There’s no industrial process that is going to take our capsules and turn them into something new, fortunately, that’s because an even better method exists. Nature.

For non-recyclable products, if they cannot be put through an energy recovery process, the landfill is the worst-case scenario. The best-case scenario is reuse or upcycling.

Biodegradable: What does it mean?

The simple answer is ‘something that will decompose naturally’.

The more complex answer is ‘any object or material, that, given time, will decompose naturally through exposure to bacteria and other living organisms’.

Bio-waste is another commonly used term to explain biodegradable materials. Human waste, animal waste, plant products, wood, paper, leaves, grass, bones, and food waste are all biodegradable.

Biodegradable is also symbolised in the form of a Mobius loop, but this time with three leaves making the triangle. Its use is not as widespread as the recycling logos.

There are six different types of biodegradation (or rather places where they occur), which is also worth noting:

- Anaerobic

- Industrial composting

- Home composting

- Soil

- Freshwater

- Marine water

What doesn’t biodegradable mean?

The biggest misconception with the term biodegradable is that some people propose the idea that ‘everything degrades eventually’. Well, that’s false information. Non-biodegradable means that the actions of living organisms cannot break it down. That’s why plastic in the oceans is not dissolving or disappearing, it is breaking into smaller pieces and wreaking havoc, but it’s still there. It’s why landfills are filling up - the majority of their contents are not biodegrading either (some materials will decompose and the methane released will be captured for energy).

Plastic is one material designed for its indestructibility, and sadly that same feature is why nature can’t seem to tackle it. Man-made plastics can only be tackled with man-made machines. In fact, in this man-made world, the percentage of materials and objects that are non-biodegradable is ever-increasing. Here are some examples:

- Plastic products like grocery bags, plastic bags, water bottles

- Metals, metal cans, tins, metal scraps, car parts

- Construction waste, rubber tires, man-made fibres

- Computer hardware like glass, CDs & DVDs, mobile phones, processed woods, laminate flooring, cables and wires

Some of the materials listed above may erode over time, such as iron sheet metal (rust), or glass (turns to sand), but they cannot be considered biodegradable because their structure does not change, they simply reduce in size. I touched upon biodegradability and how it relates to Halo in a previous article that you can read here.

Compostable: What does it mean?

Put simply, compostable means ‘something that is capable of disintegrating into natural elements’.

The full definition, with a clause that often gets left off the end, is that it is a ‘material that can disintegrate into natural elements in a compost environment, whilst leaving zero toxicity in the soil’.

As you may have noticed, biodegradable and compostable mean more or less the same thing. The major difference is that biodegradable materials will break down naturally when left alone (think of vegetable peels), whereas some compostable items require heat for the process to occur (in many cases that requires an industrial process).

Everything that is compostable is biodegradable, but not everything that is biodegradable is compostable, which is why compostable is better and should be the goal.

When is something not compostable?

Compostable has two different sub-sections that cause confusion. Industrially compostable, and home-compostable. Technically, both are compostable, but in the case of the former, materials must be collected, transported, and put through an industrial processing journey that involves machinery and high temperatures. The latter, home-compostable, signifies that materials can be thrown on a compost heap in the garden and will, in a relatively short space of time, revert to their natural elements.

Let’s use the biodegradable plastic bag that some supermarkets now offer as their ‘sustainable alternative’. You can’t put this on your compost heap because if you do, nothing will happen. This type of biodegradable plastic requires heat in order to break down.

Overcoming the phrasing

Compostable has become a buzzword in the sustainability world, posing a preferable disposal alternative to recycling and other disposal methods due to the low carbon footprint of the activity. Consumer demand for compostable materials has surged, but that has, in turn, created this confusion (or lack of awareness) between what is industrially compostable, and what is home-compostable. The confusion itself is driven by false or overstated marketing claims and a lack of clarity. The Plastic Industry has gone as far as publishing a guidance document for businesses who make compostability claims, which I recommend reading if you’re curious.

Halo’s home-compostability

Let me round off this article by saying that home-compostable is the most logical and natural progression from recycling and has, in part, inspired Halo to do what it does, to make the only home-compostable coffee capsule in home-compostable packaging. Halo’s work with a waste sugarcane byproduct has enabled them to present the world’s most sustainable coffee capsules. Whilst Halo’s competitors claim to have compostable products, they are in fact industrially compostable, as none of their capsules are truly home-compostable like the innovation that Halo has delivered.